The provided text offers an extensive overview of the book, Circuits, Packets, and Protocols: Entrepreneurs and Computer Communications, 1968-1988, which examines the foundational period of modern networking technologies. Through personal histories and technical details, the book recounts the development of key innovations like packet switching, routers, and Internet protocols during these two decades. The sources include high praise for the book’s ability to create a coherent narrative out of the complex interplay of technology, markets, and government regulation, particularly noting the anti-competitive practices of firms like AT&T and IBM. Furthermore, the excerpts highlight the crucial role of entrepreneurs, venture capital, and government initiatives such as ARPANET in fostering technological advancement and market changes, detailing the rise of early networking companies and the struggles over LAN standards like Ethernet and token ring.

This excerpt is drawn from a detailed historical account, Circuits, Packets, and Protocols, which meticulously documents the birth of modern computer communications between 1968 and 1988, emphasizing the pivotal technologies like packet switching, routers, and Internet protocols. The text weaves together three key themes—entrepreneurship, market-government boundaries, and learning—to explain the complex ecosystem that shaped data communications, including influences from regulation (e.g., the FCC’s decisions regarding AT&T’s monopoly), venture capital, and the development of core technologies such as Ethernet and TCP/IP. The book draws on extensive original interviews and documents to provide a chronological narrative of this revolutionary period, highlighting the intense competition and collaboration among early startups like Codex, Milgo, and later LAN companies like 3Com and Cisco, as well as institutional giants like IBM and AT&T. Ultimately, it contextualizes how these interwoven technical, economic, and political factors led to the pervasive influence of networking on 21st-century society.

Download the Extended Notes

Please Like, Subscribe & Share

Another Text Recommended by KJVM

The Network Effect: How a 20-Year War Between Hackers, Suits, and Feds Secretly Built the Internet

At a technology conference in 1972, a group of vice presidents from AT&T gathered for a demonstration of a strange new government network called ARPANET. Mid-presentation, the system crashed. As the engineers scrambled to fix it, the executives didn’t just look on with polite concern—they smiled. Some of them laughed. For them, this momentary failure was proof that their century-old circuit-switched telephone network was, and always would be, superior to this experimental “packet switching” nonsense [Source, p. 141]. They couldn’t have been more wrong. The fragile prototype they mocked that day was the direct ancestor of the global internet, a force that would not only make their monopoly obsolete but would fundamentally rewire human society.

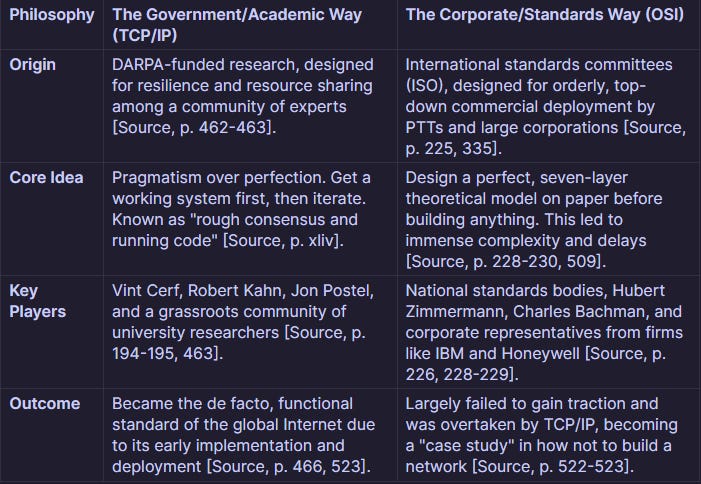

Do you know the real story of how that happened? It wasn’t a single flash of genius in a lab. The digital world wasn’t invented; it was fought for. It was forged in the chaos of three hidden conflicts that played out over two decades in boardrooms, courtrooms, and server rooms. This is the story of a hidden war between rebellious researchers, corporate suits, and federal regulators—a battle of ideas, regulations, and capital that secretly built the infrastructure of modern life. Our world was shaped by: 1) a regulatory war waged by upstart entrepreneurs against the monolithic power of AT&T and IBM; 2) a technical war between the pragmatic, grassroots TCP/IP protocol and a bureaucratic, top-down corporate model; and 3) an economic war fueled by a new class of venture capitalists who bet big on the rule-breakers. By 1988, this conflict had ignited a global market for computer communications equipment that exploded to $5 billion, setting the stage for everything that was to come [Source, p. 2].

The Foundational Conflict: Breaking the Monoliths

In the late 1960s, the digital world was a kingdom ruled by two kings. AT&T, the regulated monopoly, owned the wires—the vast telephone network that was the nation’s central nervous system. IBM, the undisputed giant, owned the brains—the mainframe computers that powered corporate America. Their dominance was not just a market condition; it was the primary obstacle to the future. Innovation couldn’t flow because the gatekeepers had locked the gates. Before a single packet could be sent, the monoliths had to be broken.

The Spark: Ma Bell’s Kingdom and the Carterfone Rebellion

For decades, AT&T operated under a simple, brutal rule enshrined in its federal tariff: no “foreign attachments.” You could not connect any device to their network that wasn’t made by their manufacturing arm, Western Electric. This wasn’t just about quality control; it was a chokehold on progress [Source, p. 25]. If you had a brilliant idea for a new communications device, you had two options: sell it to AT&T or watch it die.

Then came Thomas Carter, a Texas businessman who invented a simple device called the Carterfone. It was a cradle that acoustically connected a two-way radio to a telephone handset, allowing someone in the field to talk to someone on the phone network [Source, p. 30-31]. It was clever, useful, and completely harmless. AT&T, predictably, declared it illegal and threatened to cut off service to anyone who used it. Carter sued, setting up a classic David-versus-Goliath battle.

But this wasn’t just a plucky inventor’s lucky win. The victory was engineered by a rare breed of regulator inside the Federal Communications Commission (FCC): Bernard Strassburg. As chief of the FCC’s Common Carrier Bureau, Strassburg was a “social entrepreneur” who saw that the collision of computing and communications was not just a technical novelty, but a society-altering event [Source, p. xli, 55]. He recognized the immense potential of the Carterfone case to shatter AT&T’s closed system and relentlessly pushed it toward a groundbreaking conclusion.

In 1968, the FCC delivered its landmark Carterfone decision, declaring AT&T’s tariff unreasonable. The network, the commission argued, should be open to any device that didn’t actively cause harm [Source, p. 34, 60-61]. This decision, strategically nurtured by Strassburg, was the Big Bang for the modern communications industry. It blew the doors off the closed system.

With the regulatory dam broken, the landscape of technology was permanently altered. A series of crucial events pried open the closed worlds of communications and computing.

1949: The Justice Department files its first major antitrust suit against AT&T, signaling that the company’s absolute power was not guaranteed [Source, p. 25].

1968: The FCC’s monumental Carterfone decision legalizes the connection of non-AT&T devices to the telephone network, creating the very possibility of a competitive market [Source, p. 60-61].

1969: The Justice Department files a massive antitrust suit against IBM, targeting its practice of bundling hardware and software, which eventually forced the company to open its ecosystem to third-party developers [Source, p. 72].

The impact was immediate and explosive. In the brief period between 1968 and 1972, over 100 start-ups and existing companies rushed into the new market for data communications products, setting the stage for a technological revolution [Source, p. 59-60].

The Core Intrigue: The Packet Wars and the Standards Battlefield

With the regulatory war won and the market gates shattered, the battle shifted from the courtroom to the lab. The new question was existential: how would these new networks actually work? This was not a period of orderly progress but a chaotic free-for-all of competing visions, Cold War-era government projects, and stunning corporate fumbles. The very soul of the internet was up for grabs.

The Cold War Ghost in the Machine

The idea that would define the internet—packet switching—was born from nuclear paranoia. In the early 1960s, an engineer at the RAND Corporation named Paul Baran was tasked with a chilling problem: how to design a military communications network that could survive a Soviet nuclear attack. His revolutionary answer was to break messages into small, standardized blocks, or “packets,” and send them through a distributed, resilient mesh network. If one path was vaporized, the packets could simply find another way to their destination [Source, p. 4, 106-107].

This military-grade concept was picked up by the Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). Under the visionary leadership of J.C.R. Licklider, who dreamed of an “Intergalactic Network” connecting researchers everywhere, ARPA funded the creation of ARPANET, the first large-scale packet-switched network [Source, p. 102]. It was a government project, built by academics, based on a plan to win World War III.

The Garage Genius and the Corporate Gatekeepers

While ARPANET was taking shape in university labs, another crucial invention was born inside a corporate fortress. At Xerox’s legendary Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), a brilliant young engineer named Robert Metcalfe invented a way to connect computers within a single building. He called it Ethernet [Source, p. 208-214]. It was fast, simple, and revolutionary. But Xerox, a company blinded by its focus on copiers, completely misunderstood what it had.

Management viewed Ethernet as proprietary and integral to their office systems, not a revolutionary product to be sold separately [Source, p. 216]. Metcalfe, realizing his world-changing invention was destined to be a footnote in a Xerox product manual, did the unthinkable: he quit. He walked away from the most advanced research lab on the planet to found his own company, 3Com, with the audacious goal of commercializing the very technology his former employer had locked away [Source, p. 249-251].

This chaotic mix of military research and corporate miscalculation set the stage for the ultimate standards war—a philosophical clash between two fundamentally different ways of building the digital world.

Mainstream View vs. The Hidden Reality: The Battle for the Internet’s Soul

This collision of military projects, corporate fumbles, and philosophical debates laid the volatile groundwork for the modern digital economy.

Modern Echoes and Implications

The battles that defined the birth of the internet in the 1970s and 80s never truly ended. Their echoes are all around us, shaping the digital platforms we use every day, the fortunes of the world’s largest companies, and the very nature of technological progress itself.

The “standards wars” of that era—Ethernet versus Token Ring, the pragmatic TCP/IP versus the bureaucratic OSI—were the blueprint for the platform battles of today. The fight for dominance between iOS and Android, the cloud wars waged by Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, and the competition between social media platforms are all replays of the same fundamental conflict: will technology be open and interoperable, or will it live inside proprietary, walled gardens?

Similarly, the financial engine of the digital age was forged in this period. The explosion of venture capital that fueled the first wave of networking start-ups like 3Com and Cisco created the high-risk, high-reward financial template that defines Silicon Valley today [Source, p. 248-249]. And the government’s landmark antitrust suits against AT&T and IBM, which created the competitive space for new giants to emerge, now serve as a historical precedent as those same giants—Apple, Google, Amazon, and Meta—face a new wave of regulatory scrutiny around the globe [Source, p. 146-147, 529].

This history leaves us with a set of urgent, unanswered questions for our own time:

Did the pragmatic, “get it working now” ethos of TCP/IP doom us to an internet where security and privacy were afterthoughts, problems to be bolted on later rather than built in from the start?

As today’s tech giants become the new monopolies, are we simply witnessing a replay of the battles that broke up AT&T and challenged IBM, and will the outcome be the same?

In an era of curated platforms and closed ecosystems, have we lost the spirit of open interconnection that the internet’s early pioneers fought so hard to establish?

Conclusion

The digital world you inhabit every day was not the result of a master plan. It was the messy, unpredictable outcome of a 20-year war fought by people whose names are largely forgotten. The history of the internet is not a simple story of progress, but a series of shocking revelations:

Regulation can be innovation’s greatest catalyst. The 1968 Carterfone decision was the big bang for the entire data communications industry [Source, p. 60-61].

The Internet was born from Cold War paranoia. Packet switching was first designed to ensure military communications could survive a nuclear attack [Source, p. 106].

Corporate Goliaths consistently miss the future. Both AT&T and IBM failed to grasp the significance of packet networking, dismissing it as a niche experiment. As one pioneer recalled, AT&T’s attitude was, “When there’s a time for networks, we’ll know about it” [Source, p. 103].

Open, messy systems beat perfectly planned ones. The agile, functional TCP/IP protocol outmaneuvered the complex, bureaucratic OSI model to become the language of the internet [Source, p. 522-523].

A handful of unsung rebels built your digital world. The names you should know aren’t just the famous CEOs, but engineers and regulators like Paul Baran, Robert Metcalfe, and Bernard Strassburg [Source, p. 4, 55, 208].